Published as “Laredo vs. America (Feat. George Washington Jr.): Jesse Shaw’s Satirical Wrestling Match with Culture” on Glasstire.

During the exhibition opening for Impetus: Contemporary Iterations in Laredo Right Now, curated by Maritza Bautista for the Martha Fenstermaker Memorial Visual Art Gallery in Laredo, artist Jesse Shaw brought focus to a varied set of personae in relation to one another, as well as to multiple combined artworks in a performed “unveiling.” Shaw first addressed gallery visitors as the assistant to George Washington Jr. (GW Jr.), a fictional alter-ego who, in turn, confuses Shaw’s name for “Joseph Shawn.” He welcomed all into the “historic [and] surreal occasion” of unveiling the “official portrait” of GW Jr., hidden behind red fabric.

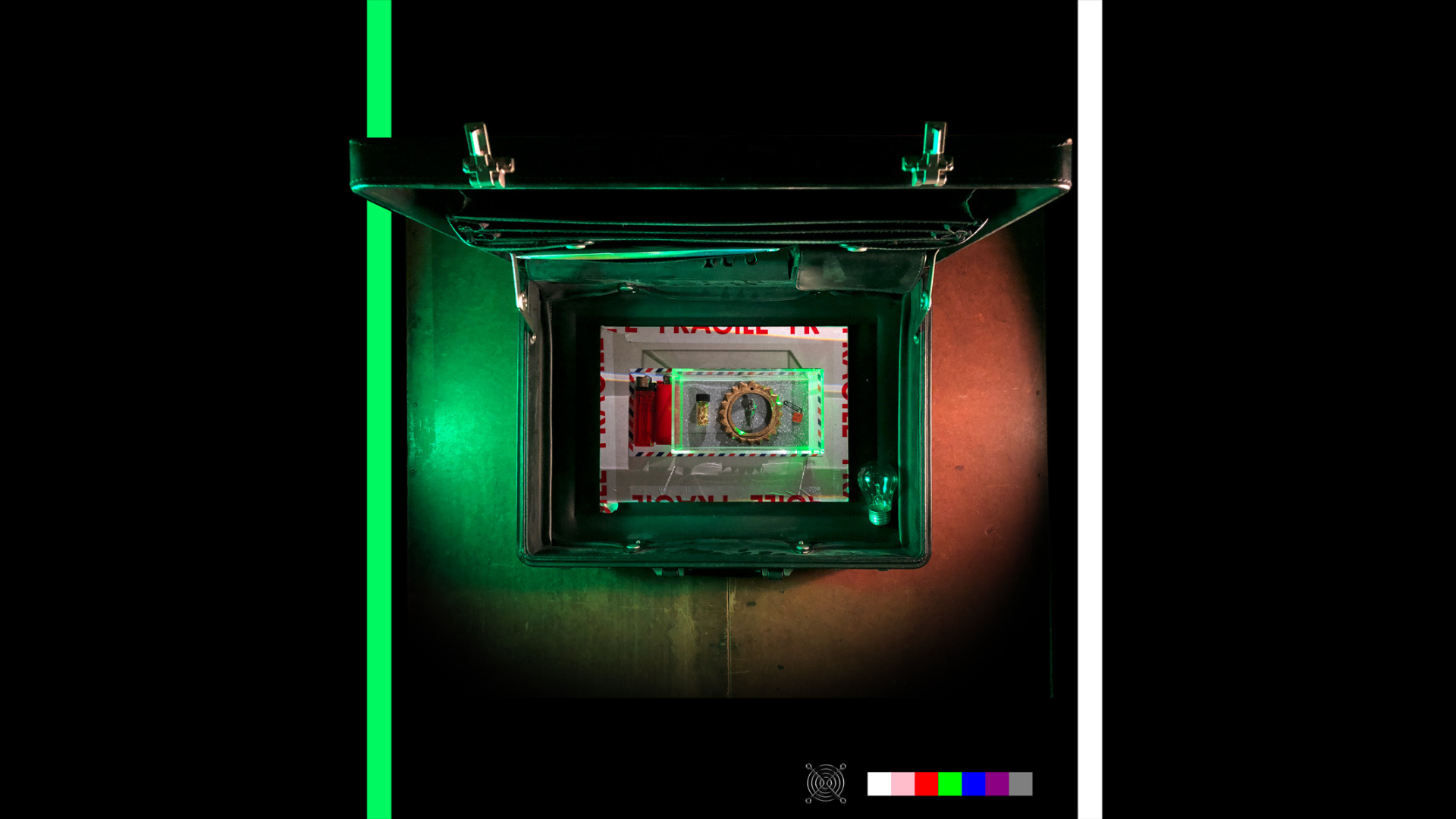

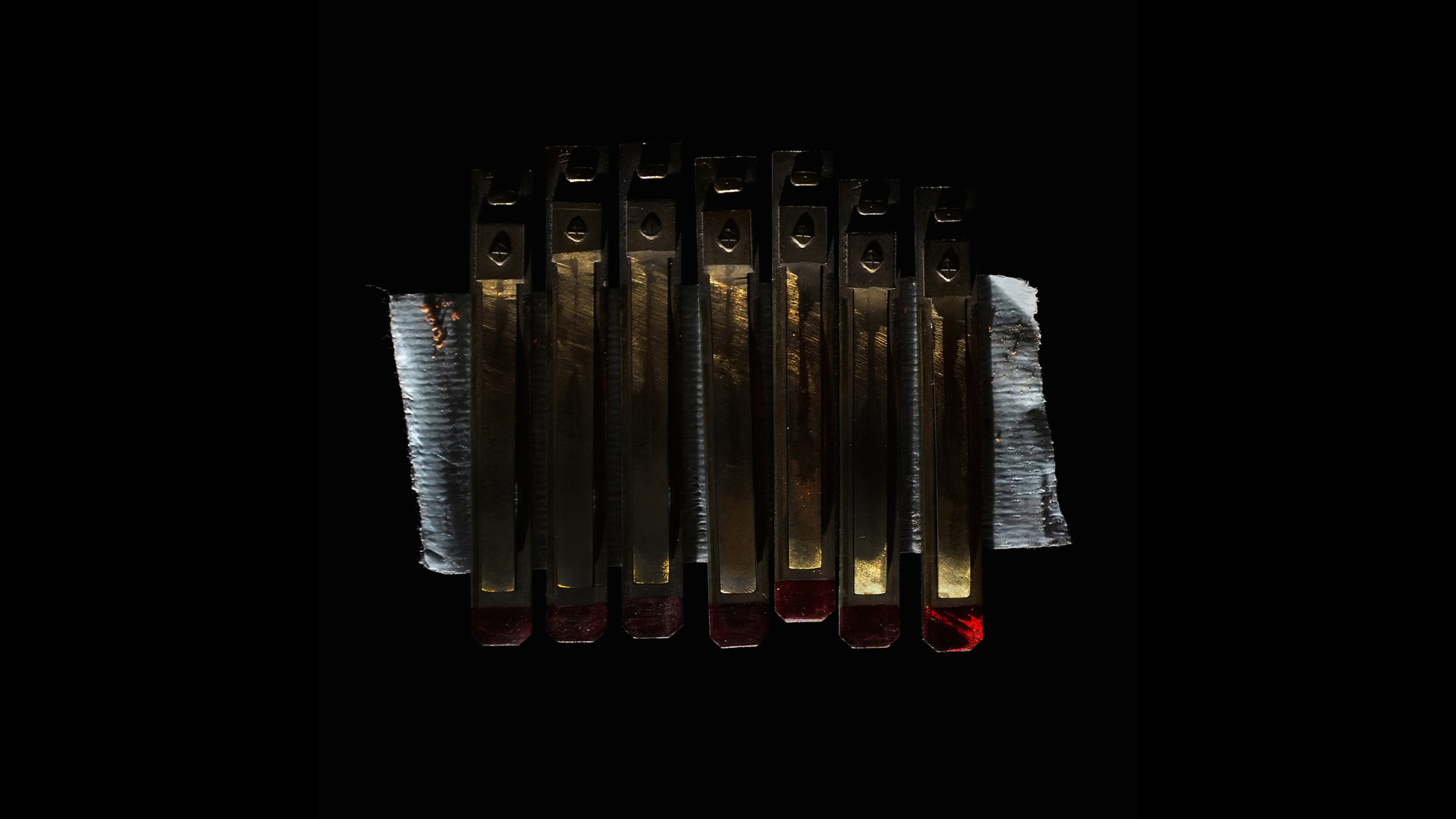

The work revealed by Shaw and Bautista turned out to be a Face/Off-style split portrait with the words “LOSER” and “JESSE SHAW” on opposite sides of the figure representing GW Jr. and a tarred and feathered Shaw, respectively. Confused yet amused, visitors cheered at the spectacle. In a gesture of playful birthday stage magic, a queasy Shaw exited the gallery to then re-appear in costume as an arrogant GW Jr. As such, and in disdain after encountering the mocking portrait, he proceeded to open a “retribution-smelling” can of tomato soup (neither Campbell’s nor Warhol’s) with a “can opener of freedom,” and splashed it on the artwork. Then, he staple-gunned a printed ChatGPT-generated image of himself over the stained artwork. That image was created from a description mentioned by George Washington Jr. in an Instagram video posted just days before the performance. In cartoonish celebration, he forced dollar bills on visitors as “bribery.” Those bills featured GW Jr.’s image in place of George Washington’s, and “Laredo, Texas” in place of “United States of America.”

The soup-dripping white gallery walls signal Shaw’s explosive approach to his own work through the GW Jr. persona: a chaotic spill of image variations and scattered performances, both online and in person. What may at first resemble an infantile comedy skit reveals itself as a culmination of meditative layers: GW Jr. as conjured by AI as prompted by GW Jr.; GW Jr. as embodied by Shaw, both in image and performance; and Shaw in disguise as Joseph Shawn, GW Jr.’s “assistant.”

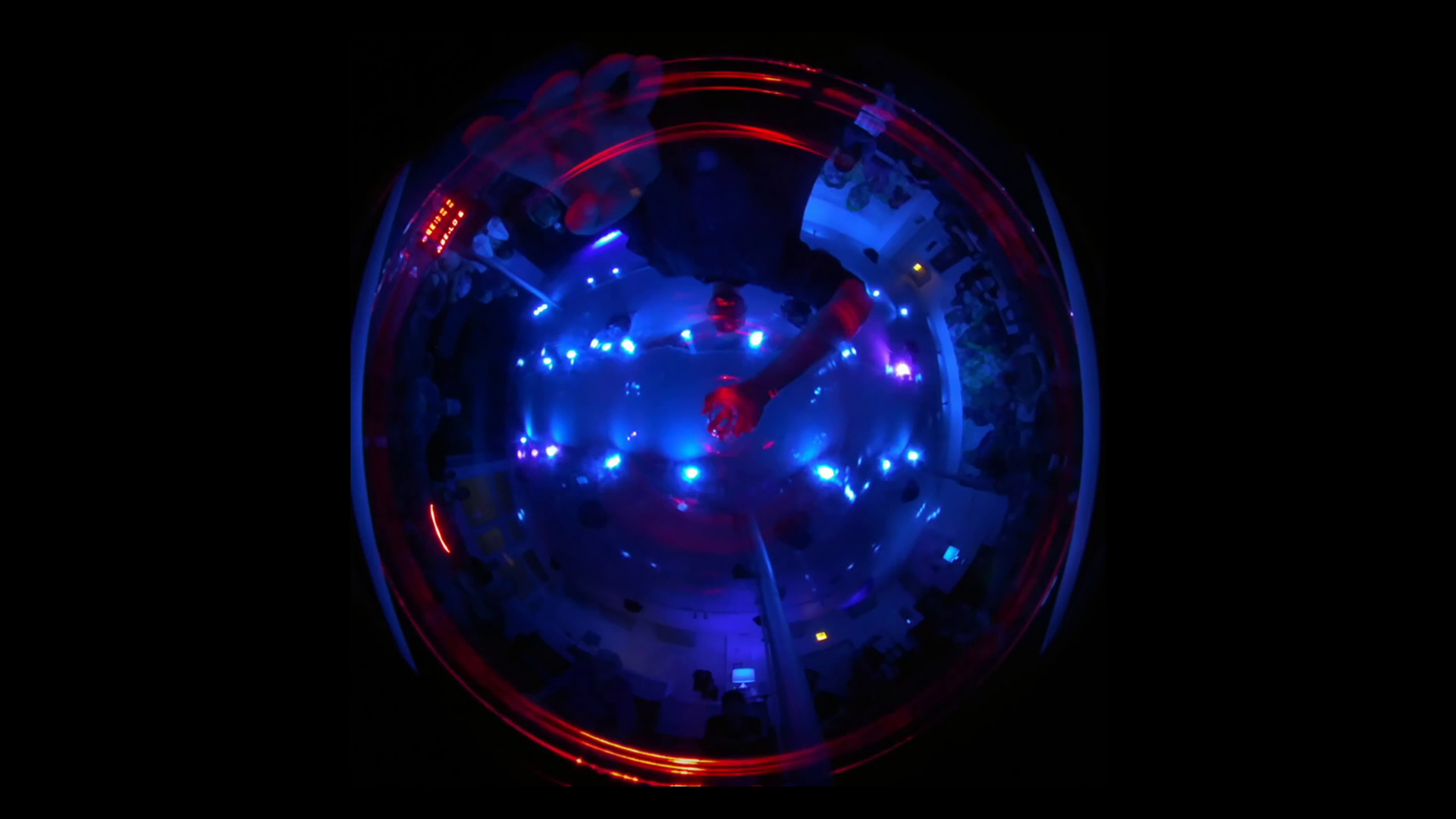

Shaw conceived GW Jr. as a contribution to Laredo’s wrestling community, of which he and his family are fans, and Luis “Spartan” Ramirez, owner of Five Star Wrestling took on the idea, bringing the character into the ring during his matches. GW Jr. performances are not limited to the gallery and the wrestling ring, but also pepper the online sphere. A social media frenzy began in late spring 2024 as a satiric take on meme culture and, in Shaw’s jab to Washington Birthday Celebration Association (WBCA), “border-colonial content” creation, including AI-generated images and common tropes like selfies and videos shot all over Laredo. Shortly after, he debuted live at the Five Star Showcase III at the VSR Arena. Shaw’s performance at Impetus focalized all of these modes of presence, transposing the high energy drama of online viral culture into space, including anticipation, shock factor, museum artwork vandalism as protest, money giveaway, rant, prank, cringe, and self-obsession. Total saturation.

The character of GW Jr. is less a reference to the historical George Washington than a parody of his questionable afterlife in the tradition of Laredo’s WBCA, established in 1898. For some Laredoans, the WBCA’s pageantry is symbolically disjointed historical fantasy. For others, it is a respected tradition and meaningful inheritance.

Shaw’s GW Jr. may arguably be not solely an artistic persona (as inspired by Tim Rubel’s 2024 exhibition Thirst at Texas A&M International University, and hinting at Guillermo Gómez-Peña’s performance art), but also an entertainment one (inspired by the question of “who would make a great Laredo wrestling villain?”), hinged by a two-way satire, binding artistic and wrestling contexts. GW Jr. makes bombastic appearances as promoter and emcee of wrestling matches, alluding to both American pro-wrestling and Mexican lucha libre. A chair at Impetus read “This seat is reserved for George Washington Jr., Member of the Societal Elite and Wrestling Manager.”

These confrontational and cascading layers of identity are rare in Laredo art, but not absent in its multifaceted border culture/cultura fonteriza. They can be noticed in WBCA’s yearly celebrations, including colonial-themed pageants and balls celebrating George and Martha Washington and Pocahontas, The Abrazo Ceremony, el paradeque no puede faltar, and the Jalapeño Festival, among other festivities. This is in spite of the fact that, according to ChatGPT, “George Washington had no personal, military, or political connection to Laredo, Texas, as it was part of a Spanish colonial region that was entirely outside of the sphere of influence of the early United States.” Furthermore, “there’s no historical evidence that George Washington had any involvement with or exposure to jalapeños. Any connection would be symbolic or humorous, not factual.”

It doesn’t matter.

Shaw superscribes such a bewildering state of affairs with spontaneity and wit, using locations throughout the city of Laredo as stages for comedy and critique as GW Jr. The results are trashy and engrossing. Everyone seems to get the big joke, yet Laredoans are keyed in to its nuances. Shaw is not alone, and neither are We, The People. After all, the world outside is just as perplexed by Laredo’s fixation with and investment in the Washingtons, as demonstrated by award-winning filmmakers Cristina Ibarras and Erin Ploss-Campoamor in their 2014 PBS documentary Las Marthas.

During the performance at Impetus, Shaw as GW Jr. mentioned that his portrait (again, fictionally created by “Joseph Shawn,” his assistant, who is almost indistinguishable from Shaw) was a “gross distortion.” Distortion and scale are prominent features in Shaw’s works on paper in the exhibition: Large Commemorative Plate (large meaning 4 x 4 feet and other small plate-sized versions), George Washington Jr. Project Scare the Bejeezus (the big head) (big meaning 4 x 8 feet), among other ephemera.

A pillory stands in the gallery referencing its role in GW Jr.’s wrestling performances, which have also been staged in art venues such as the Laredo Center for the Arts. Its stark presence encapsulates a central theme: (self-)humiliation as public spectacle. As if locked in the pillory, Shaw’s hyperbolic face and physicality is pushed to the extremes in all modes of presentation of GW Jr., both on and off screen and on and off the wall.

And it’s fun.

But Shaw also subverts such references, critiquing artists’ self-perceptions and their battle for attention amid social media content and art practice. In context of the border/la frontera, GW Jr. makes sense as a product of both Laredo and Americana. Its resonance with President Donald Trump’s political entertainment and peer pressures are hard to dismiss. Whether from the perspective of Coke or Pepsi, Trump distorts reference points for civil discourse, polarizing the masses as both savior and devil, while maximizing his status in reality TV and the World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) Hall of Fame. In 1992, George Washington was posthumously honored as a Distinguished Member by the National Wrestling Hall of Fame. Enter Shaw’s transfer technique into GW Jr.

When asked about the origins of GW Jr., Shaw replied, “I’ve always wanted to be in a play.” The line echoes Trump’s recent whim to reopen Alcatraz as a prison because, as he put it, “I guess I was supposed to be a movie maker.” According to Shaw, GW Jr. and Trump “share several character flaws.” Hubris or honesty, this also recalls the glee with which today’s billionaire male figures chase their childhood dreams, from Jeff Bezos’ “Ever since I was five years old, I’ve dreamed of traveling to space,” to Elon Musk’s boyish admission that he wanted to make money to play better video games. KEEP OUT: Dreamy Boys’ Club.

GW Jr. seems to be modeled less on Washington than on Trump, though both function more as symbolic stencils than historical figures. In Shaw’s web of references, both Laredo and America become distortion points, warping sociopolitics and public personae into theater. Drawing from the already fantastical WBCA version of Washington and Laredo’s wrestling and golfing communities, Shaw amplifies Trump’s brand of America: aggrandizing, chaotic, and obsessed with winning and humiliation, both of others and of self. But there’s nothing wrong with dreaming.

Shaw uses GW Jr. for cultural commentary, often referencing recent events. He has thrown fits from alleged rejection from the Country Club, dramatized thumb-wrestling tournaments, and unveiled an artwork as Trump would the Declaration of Independence at a Huicho Domínguez-style Oval Office. Cleverly, the latter gesture follows Trump’s portrait fiasco as he, meta-ironically, deemed it “purposefully distorted” by its artist Sarah Boardman, replacing it with one by Vanessa Horabuena, “a “Christian worship artist” who has also depicted Abraham Lincoln, Mount Rushmore, and Jesus Christ. Similarly to controversial artist Andres Serrano’s The Game: All Things Trump (2018-2019), Shaw activates the access, status, and ambivalence that satire may have in different contexts. It seeps through.

“When they let me in, I’m letting all of Laredo into the Country Club, I’m letting all of them into the Washington Society, because we’re the elites, and we’re gonna’ box them out.”

George Washington Jr., Tragaluz, vol. II, no. 1

“I don’t know if I believe that if he gets in, he’ll actually open up the Country Club to everybody else.’”

Jesse Shaw, Tragaluz, vol. II, no. 1

Aestheticizing bad taste into a surreal extravaganza while holding a mirror up to Laredo culture, Shaw’s GW Jr. releases a hodgepodge of simulacra and its powers to absorb the artist. Shaw’s background as a printmaker further reveals this, as the printmaking medium itself can be synonymous with duplication, loss, and degeneration. Aside from depicting GW Jr. in a DIY style, Shaw’s other printmaking work is rather exacting, including the 50-part series American Epic (in progress since 2008). Pushy Palm (2021), a work involving silkscreen, wood, and printed vinyl, cites Laredo’s palm trees, which, not unlike the various perplexities already mentioned, are not native to the area, but planted for aesthetic purposes, including the Washingtonia robusta (Mexican Fan Palm).

Shaw imprints his GW Jr. persona across media and contexts through traditional prints, AI-generated images, and crude, simulacra-fueled, semi-improvised performances. Each impression raises new questions about image, persona, and the role of the viewer as participant. Laredo culture itself becomes a kind of tool in this process, like a silkscreen, something through which meaning is transferred, distorted, and replicated. At the same time, Shaw works to exhaust the theater of politics, pushing it toward absurdity and collapse, all while staying attuned to artistic and performative references. Most recently, GW Jr. has directly cited Andy Warhol’s performance in Jørgen Leth’s experimental film 66 Scenes from America (1982) and sampled “Mean Gene” Okerlund’s 1985 WWF (now WWE) interview with Warhol. As a printmaker, Shaw explores not just what gets printed, but where and how impressions land, across surfaces, spaces, and publics.

Shaw’s gestures show what Laredo art can be, how Laredo is, and what politics have become: balderdash. Like a Cinco de Mayo brunch seasoned by The Onion, Shaw shakes conventions of elitism and belonging through artistic diversion. And permissibly so — he is a minority gringo artist in a town that is 3.19% non-Hispanic white. He was born in Georgia, grew up in Hawaii and along the Kentucky/Tennessee state line, and was based in Durham Township, Pennsylvania before moving to Laredo. His website is proudly titled American Printmaker. Native or transplanted, to be #LaredoProud is to accept dichotomy and discrepancy, no hay de otra.

GW Jr.’s artificial portrait sits atop a portrait vandalized by its own subject, layering AI hallucination over artistic fancy. ChatGPT informs us that George Washington had no connection to Laredo or jalapeños, but he may have enjoyed tomato soup. What matters here is not fact, but friction, and GW Jr. is an incisive celebration of this condition, whether it makes sense or not.

In his book Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth, and Art (also subtitled How Disruptive Imagination Creates Culture), author Lewis Hyde states that the trickster archetype not only pervades, but creates and endlessly reshapes the world, never finishing it. For poet Margaret Atwood, “tricksters are a great bother to have around, but paradoxically they are also indispensable heroes of culture.” In this vein, liminal performers appear during times of cultural dissonance and transition.

Shaw’s GW Jr. offshoots from his main line of work, triggering cultural reflection of what destabilizes and allures us today. Seeking to further captivate audiences while combining communities in Laredo, Shaw envisions capturing GW Jr. in a grand mockumentary. And he is not lying. Until then, anyone with a staple gun, a can opener, or a hammer, looks forward to liking, sharing, subscribing, and hitting that little bell of freedom.

Pass the popcorn!

Impetus — a group exhibition also featuring works by Sandra Amoabeng, Emily Bayless, Jorge Javier López, Marcela Morán, Emily Rice, and Gil Rocha — is on view at the Martha Fenstermaker Memorial Visual Art Gallery in Laredo through August 22, 2025.

–Noé Cuéllar