How does action relate to its driving forces?

How does proportion shape the viability of action?

To what ends might power relations be repositioned?

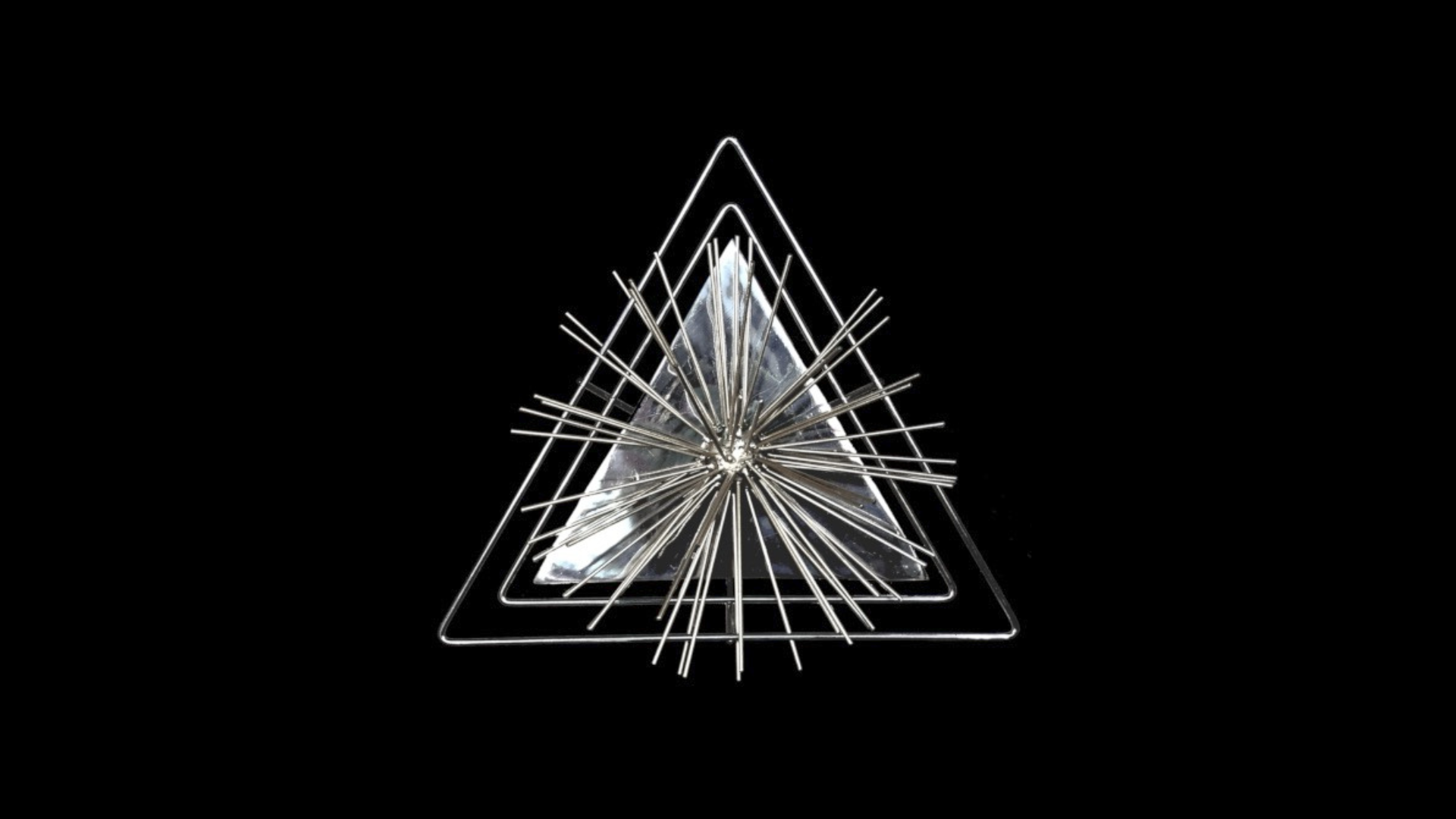

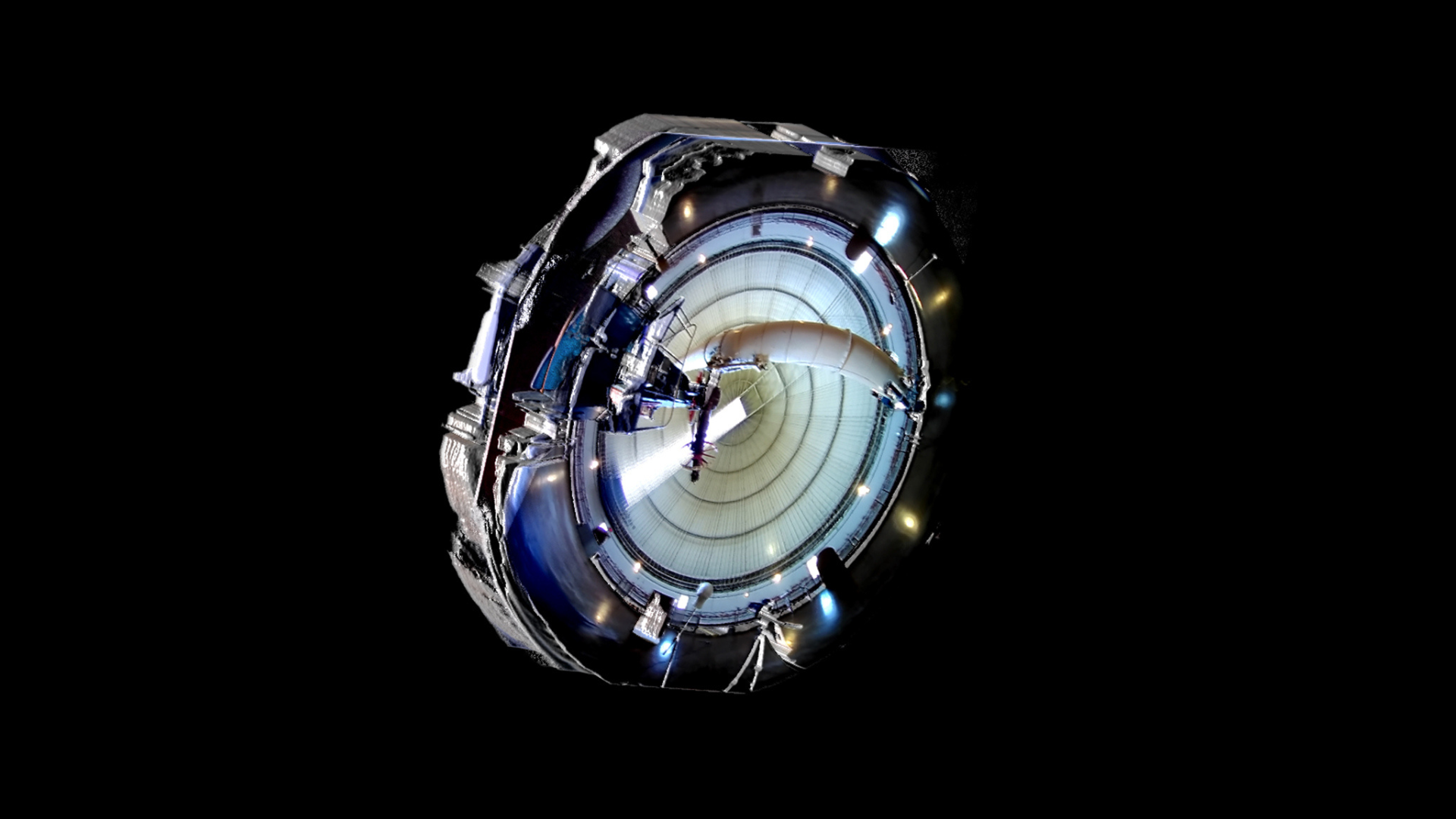

Chilean artist Mauricio López F.’s exhibition Wind Reenactment raises these questions across three central “figures.” Upon entering the space, the exhibition feels almost like stepping into a schematic drawing. Three main installation zones—described by the artist as “exemplary objects”—are labeled Fig. 1, Fig. 2, and Fig. 3 in large script. Around them, four smaller pieces are placed on a wall, in two corners, and in the gallery’s exterior (visible from within).

Though discrete, the three figures build upon one another, accumulating meaning and scale. Varying in media—from mechanized objects and sound installation to cast cement and printed fabric—they construct a network of futile, often disproportionate, relations between form, force, and function.

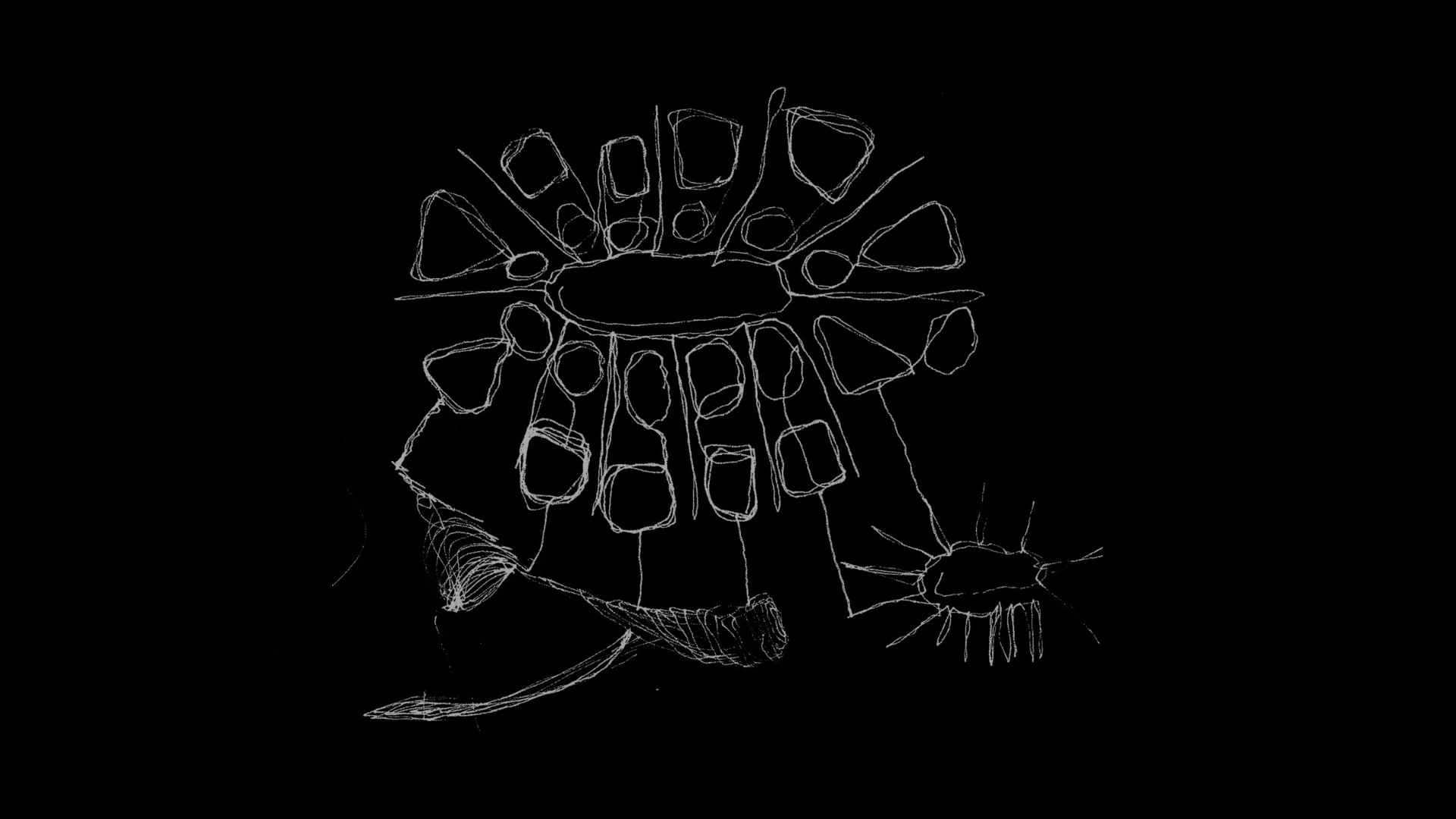

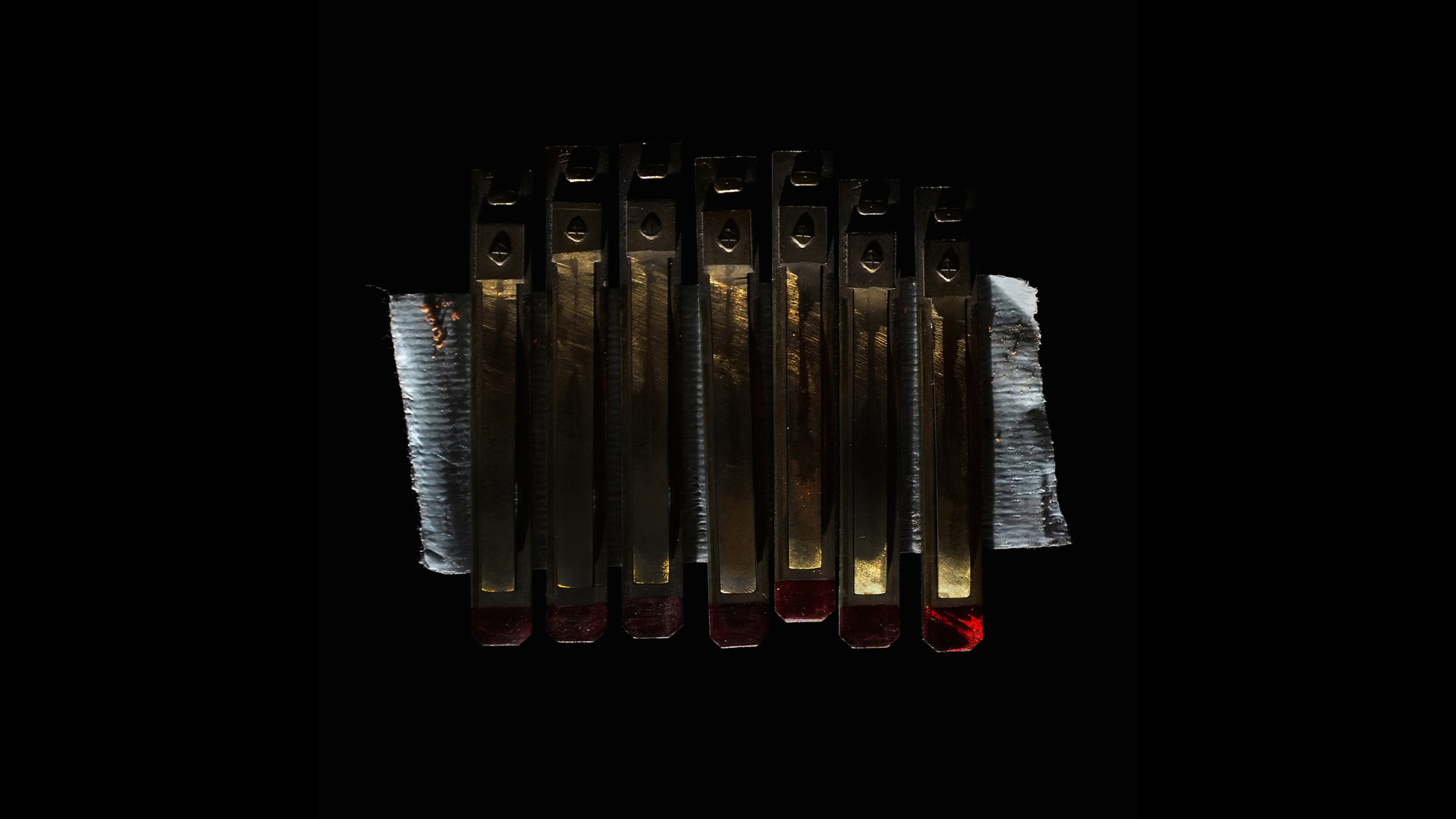

Fig. 1 juts from the wall like a fragment of a banister. A single broken baluster is weakly animated by a miniature white flag on a twisted pole, powered by a noisy mechanism of wheels and chains. The movement it produces is slight, yet the mechanical system behind it is substantial and loud. The imbalance between energy and outcome verges on the absurd, as if the flag were gently checking the baluster for signs of life. And yet, the action unmistakably ‘is.’

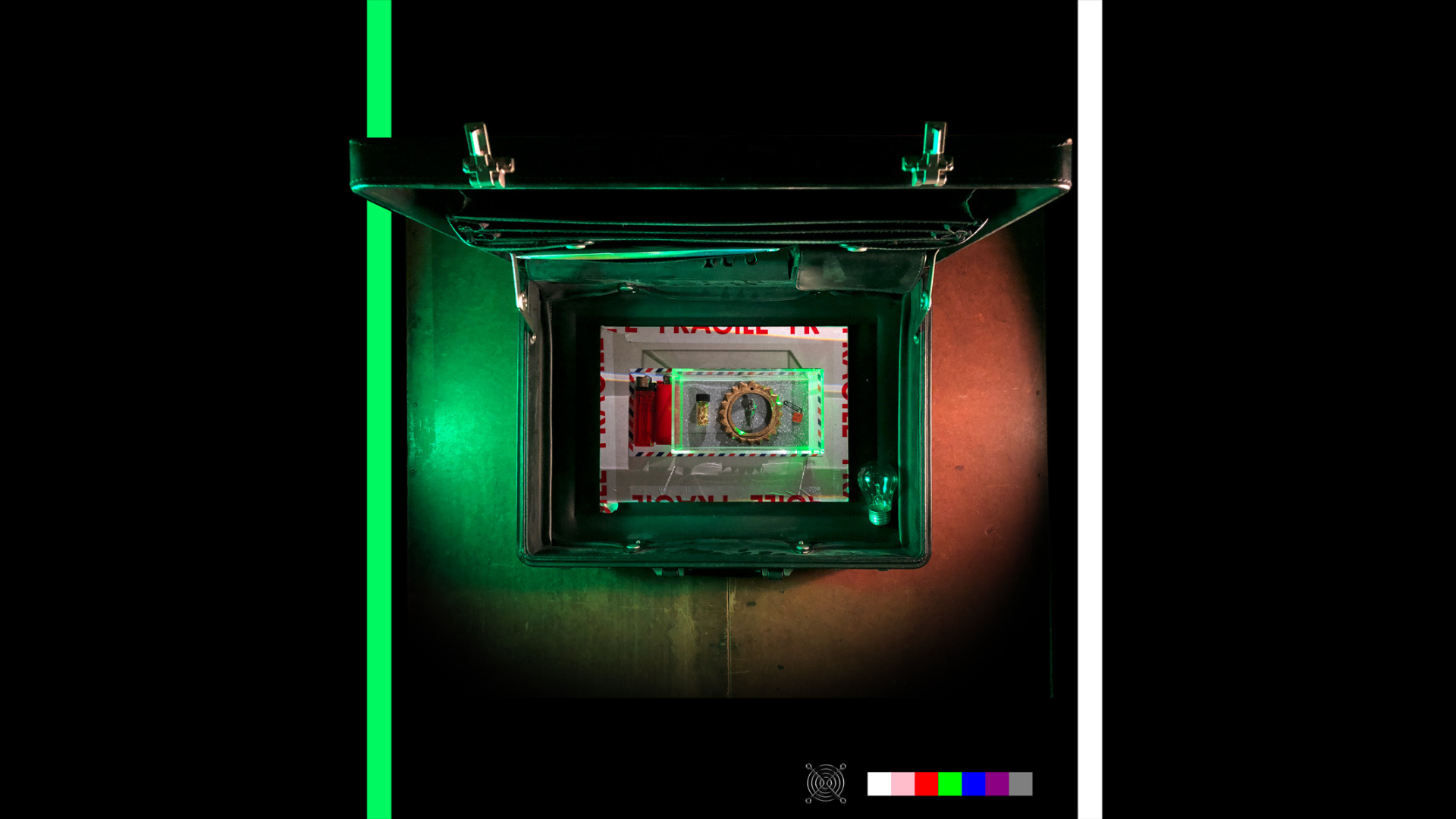

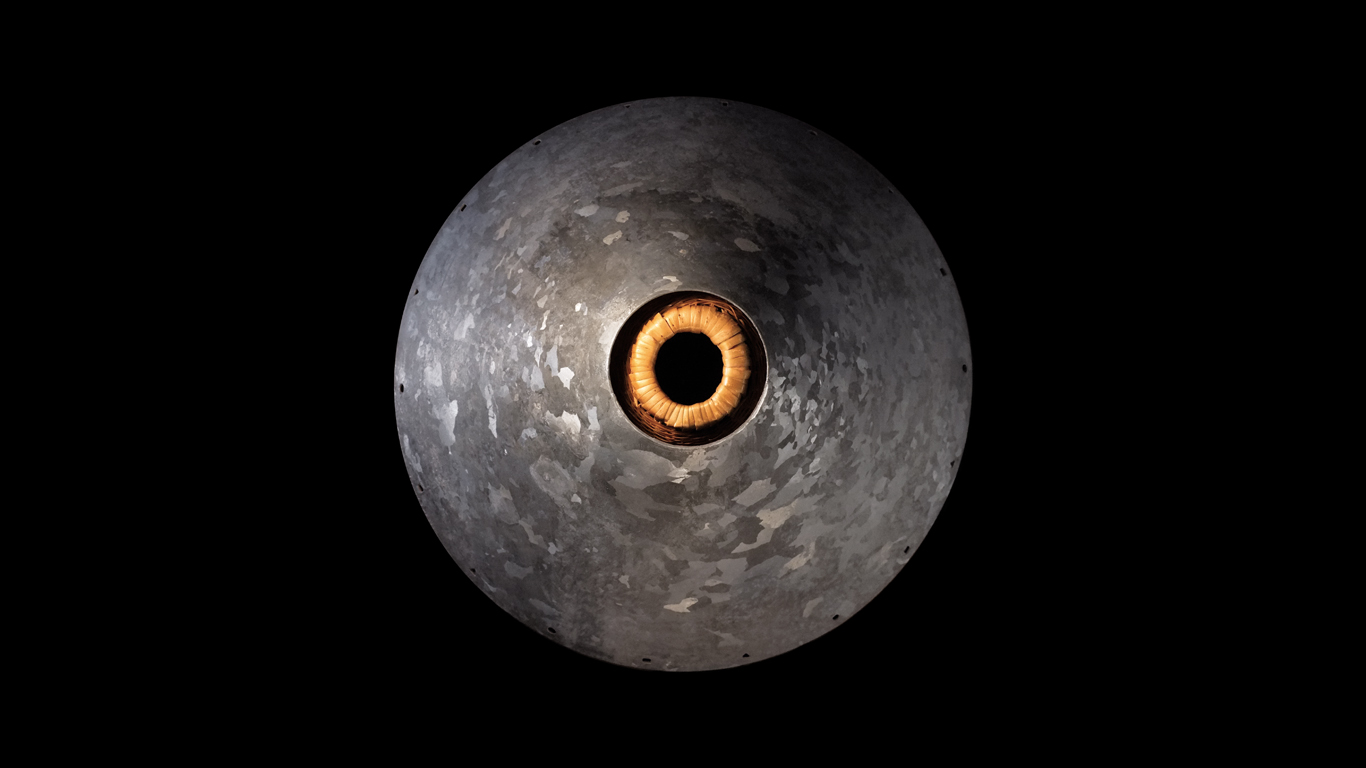

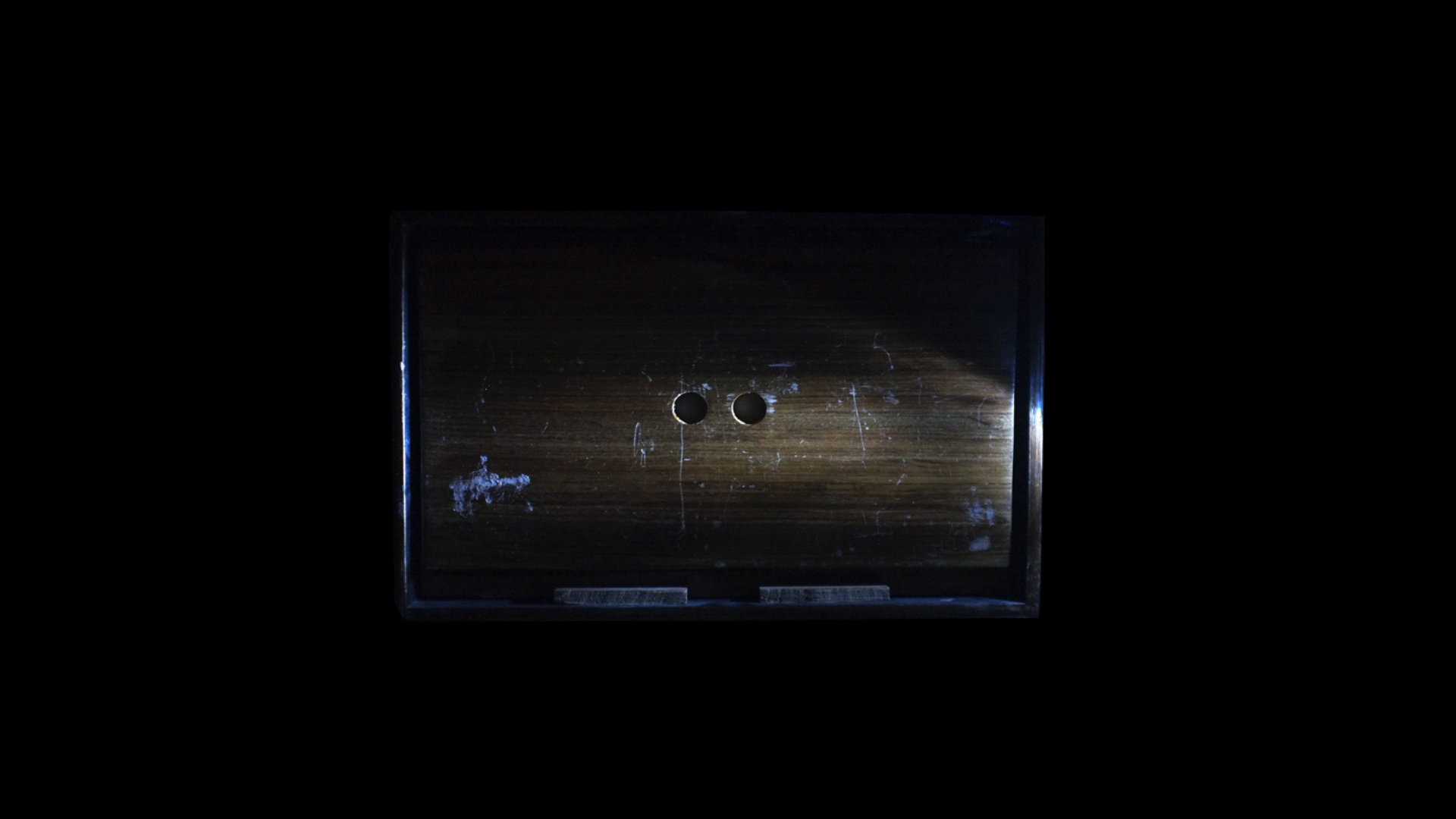

Fig. 2 expands on this logic, presenting an ineffective action within an ironic frame. A vintage chest—repurposed as a loudspeaker—rests on its side. Inside it, another miniature white flag faces the source of sound behind plexiglass. The chest emits a loud, persistent rumble, yet the flag remains still. Sound cannot be contained within its frame, and the flag—perhaps signaling a truce—registers no effect. Lopsided, this image of disconnect evokes a deafened state.

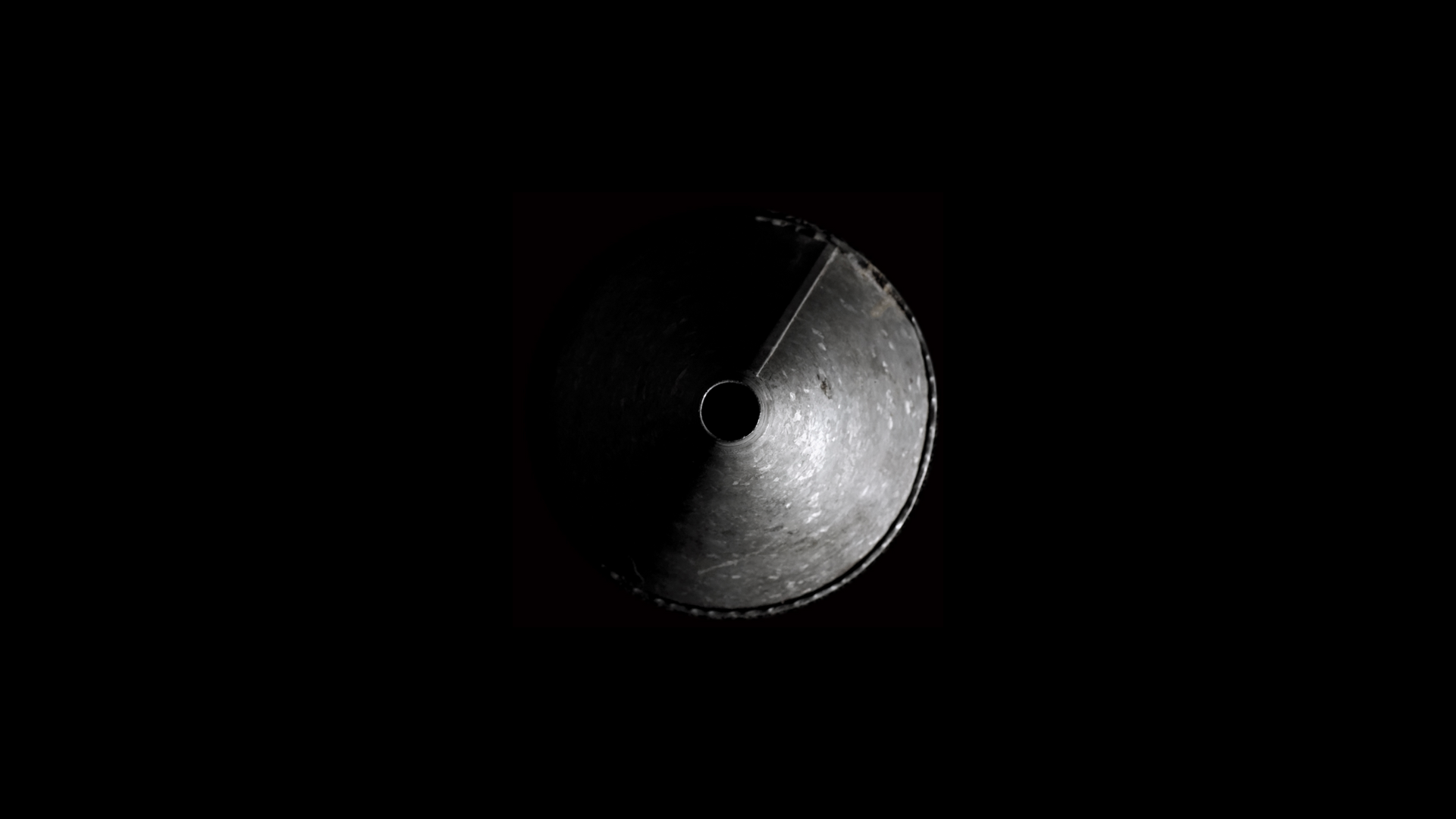

Installed on the wall opposite Fig. 3, both Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 are silent and inactive upon entering the gallery. Each can be activated by flipping its corresponding switch. Their quandaries shift in scale in Fig. 3, which presents a broken electrical switch behind a clear acrylic box. Next to it stands a full-sized flag bearing an obscure photographic image, affixed to a pole. Here, the switch is plainly severed from any function. Meanwhile, the flag is accessible but untethered to any evident system. Is it free?

While the acrylic case clearly renders the switch (which is switched on) inaccessible, López notes that he periodically dusts the box for fingerprints—checking, perhaps, for signs of desire to trespass, to bring about an action, to flip the switch, to enact change, to initiate movement. Yet in this figure, action upon the flag arrives only by direct contact with it, or by means of the wind through the gallery doors.

This forensic sensitivity extends outward from the three-part display toward three smaller cast cement pieces on the wall and corners. While the noise of Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 fills the space, these peripheral objects seem to function as listening points, redirecting attention toward the gallery’s very wet acoustics. To observe them closely, one must literally turn away from the main display, thus filtering the noise. These fragments are discarded yet relevant prototypes in the development of the larger works.

While not overtly political, Wind Reenactment carries power dynamics that surface gradually through its conceptual syntax. The work stages stark, often satirical responses to heightened and miniature conditions. It suggests that agency is entangled with an awareness of proportion—sometimes deeply out of balance—and that action may reside just as much in symbolic observation as in decisive intervention.

According to López F., the figures in Wind Reenactment attempt to recreate “the tensions between misinformation and the drive to capture.” He writes:

Possession is an impulse that quickly settles into control. Inevitably, what is not understood is captured, examined, and when it presents some exploitable quality, it becomes a tool, a possibility. Wind is a strongly romanticized element, allowing heroism to be injected into moments that might otherwise seem tasteless. At the same time, its manifestation has a revealing quality. It dusts off what is latent and shows us that our environment is not pristine—that there is the precarious, the hidden, the forgettable, the unfixed. This duality forces its will upon us; we cannot stop it—it is there whether for our convenience or not. We can try to simulate it in forced controlled conditions, but it is well known that that’s not wind.

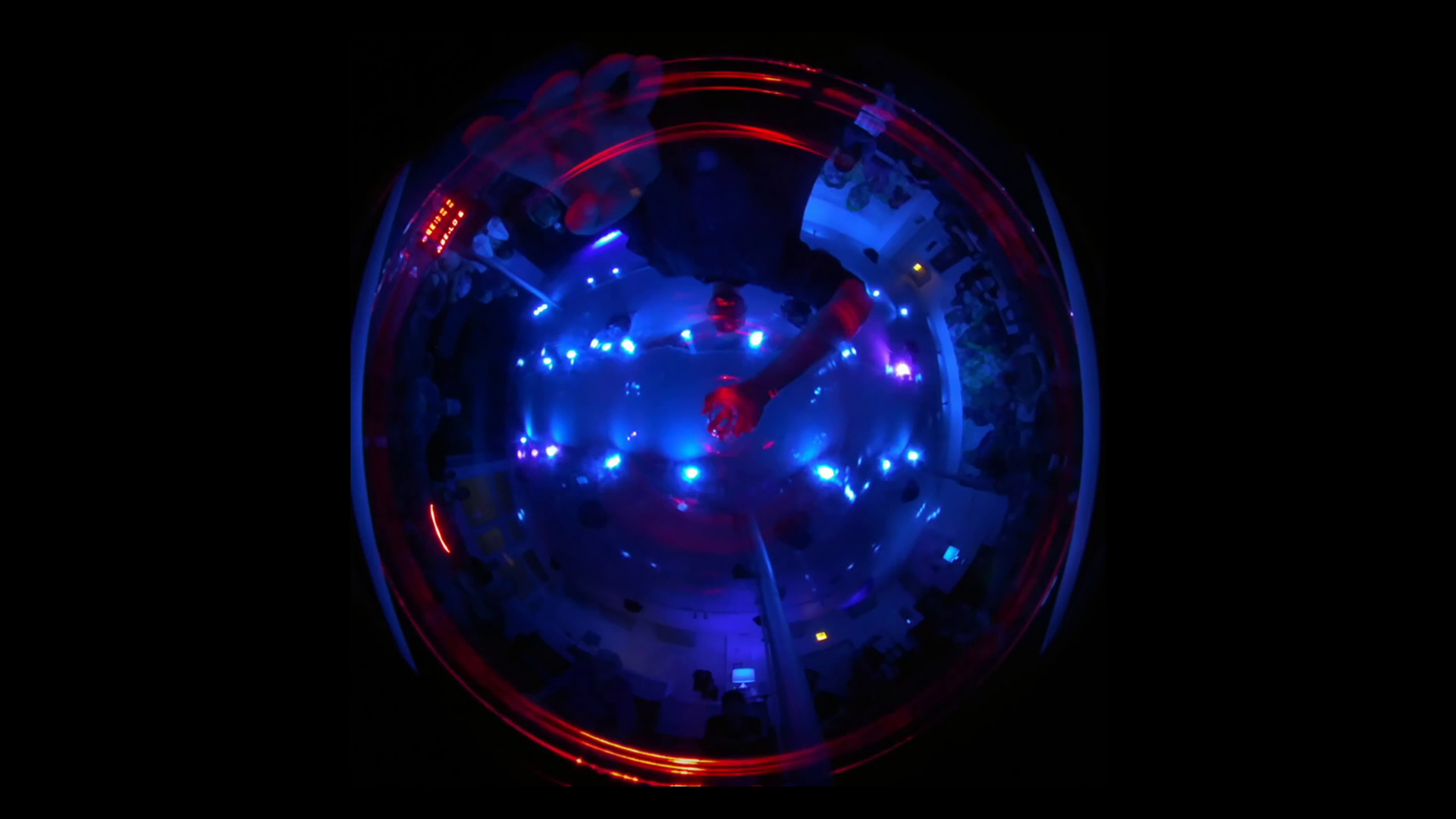

Across various other projects, as in También Tienes Que Venir Mañana / You Also Need To Come Tomorrow (2025), political factors appear in symbolic tensions and humorous hints alike. The performance Repite Después De Mí / Repeat After Me (2024), presented for Museum Church at the National Museum of Mexican Art, strikes a balance between spontaneous community and infrastructural codes, redirecting the notion of liturgical call-and-response by presenting the audience with a graphic score that guides their participation. While López F. leads the performance, the audience is involved nonverbally through the simplicity of the score’s abstractions and the flow of sonic gestures. Controlled yet effortless, participation emerges more naturally than hierarchically, as the audience intuitively recognizes openings for response, blending collectivity with the simplest of utterances.

The integration of the audience in the Repite Después De Mí / Repeat After Me performance is echoed in Wind Reenactment‘s activation of resources, where signals, reappearances, and variations correspond with shifts in space and scale—an allusion to reverberation. López F.’s work carries distinctly sonic and allegorical qualities—not through fixed meanings, but through conceptual triggers that accumulate across objects, gestures, and scales. These works propose relational structures that mirror political and affective conditions, filtered through a combination of simplicity and whimsical absurdity.

Let the wind blow, and let the flip switch you.

Wind Reenactment is on view at Comfort Station, Chicago, June 7–29, 2025.

–Noé Cuéllar